Core terms

As this article contains a lot of terms that are very important for understanding Kerberos and Active Directory, I will explain them first.

Principal

A principal is an identity in Kerberos. In Active Directory, this typically maps to a security principal (user, computer, service account). The practical implication is that a principal has a long-term key (derived from its password) that the KDC uses when issuing tickets.

Realm

A realm is the administrative and cryptographic boundary in Kerberos. In Windows environments, it usually maps to an AD domain (DNS name uppercased). The protocol foundation is Kerberos V5 as defined in RFC 4120.

KDC

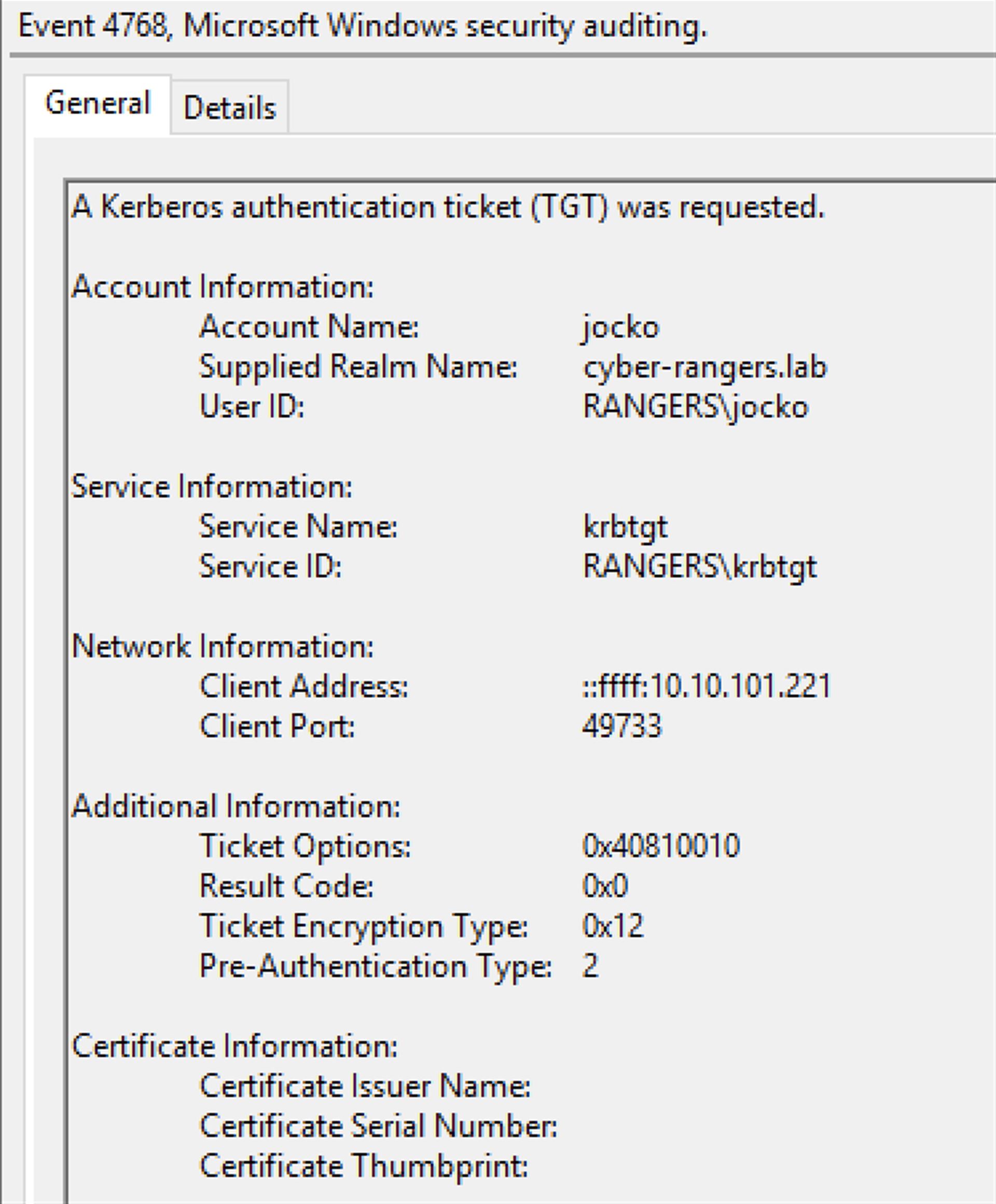

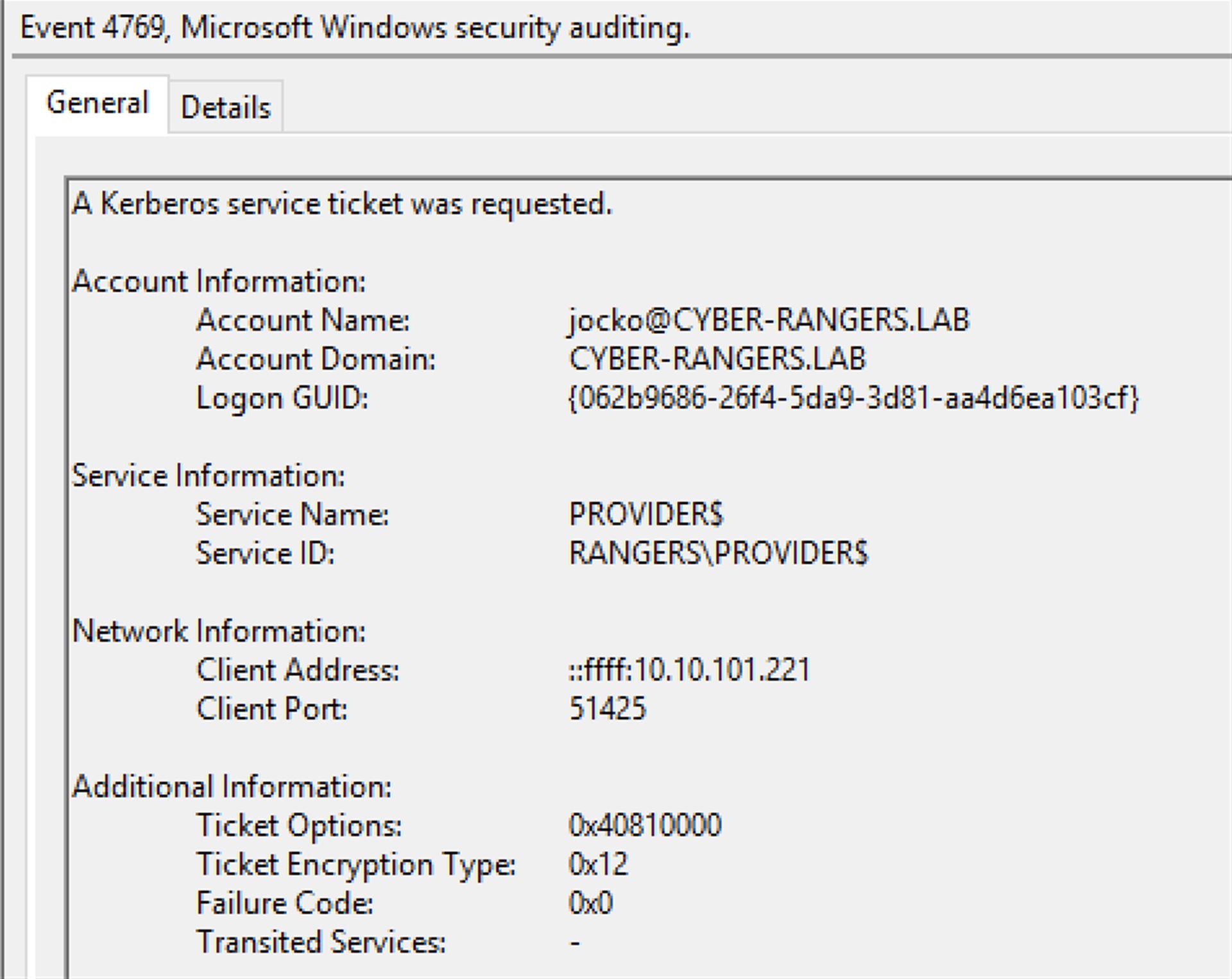

The Key Distribution Center (KDC) issues and validates Kerberos tickets. In AD, the KDC role runs on each Domain Controller (DC). Kerberos V5 authentication is built around the AS, TGS, and AP exchanges described in RFC 4120.

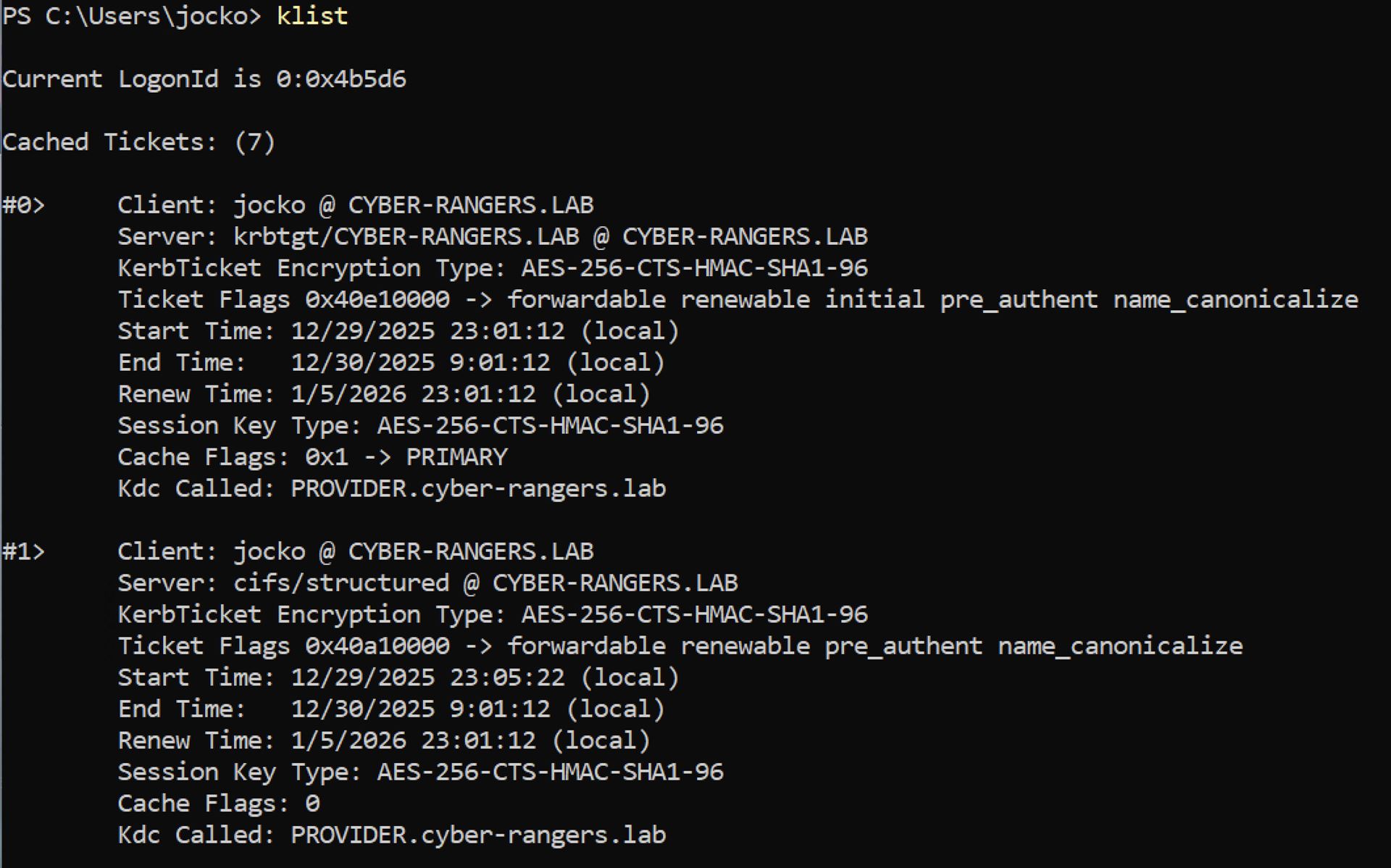

Ticket, TGT, service ticket

A ticket is a credential intended for the server side and is typically encrypted with the long-term key of the target service, not the client. A TGT is a special ticket for krbtgt/REALM and is used as input to the TGS exchange. A service ticket is issued for a specific service (commonly identified by an SPN).

PAC

The Privilege Attribute Certificate (PAC) is a Windows extension that carries authorization data (for example, group membership) inside Kerberos tickets. This is central for building the Windows access token.

PAC validation

PAC validation is a process where the server-side OS forwards PAC-related verification to a Domain Controller. Microsoft’s MS-APDS describes that the OS forwards the PAC signature from the AP-REQ to a DC in a message such as KERB_VERIFY_PAC, and the DC returns the result.

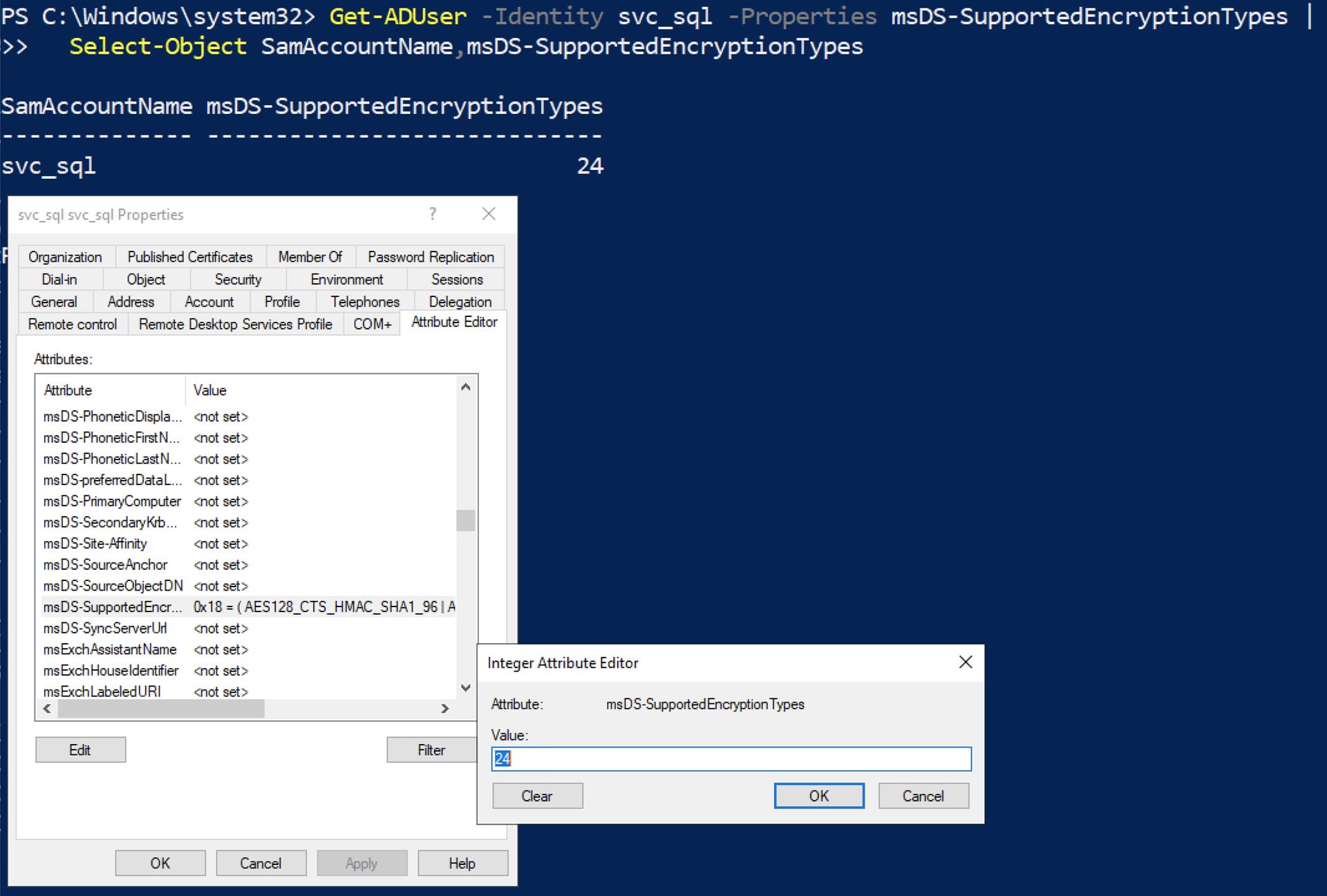

Etype

An etype (encryption type) defines which crypto profile protects a ticket. In AD, etype is not only a crypto choice; it’s also a configuration and detection signal (baseline vs deviation). Microsoft defines msDS-SupportedEncryptionTypes as describing the etypes supported by user/computer/trust accounts and notes KDC uses this when generating service tickets.

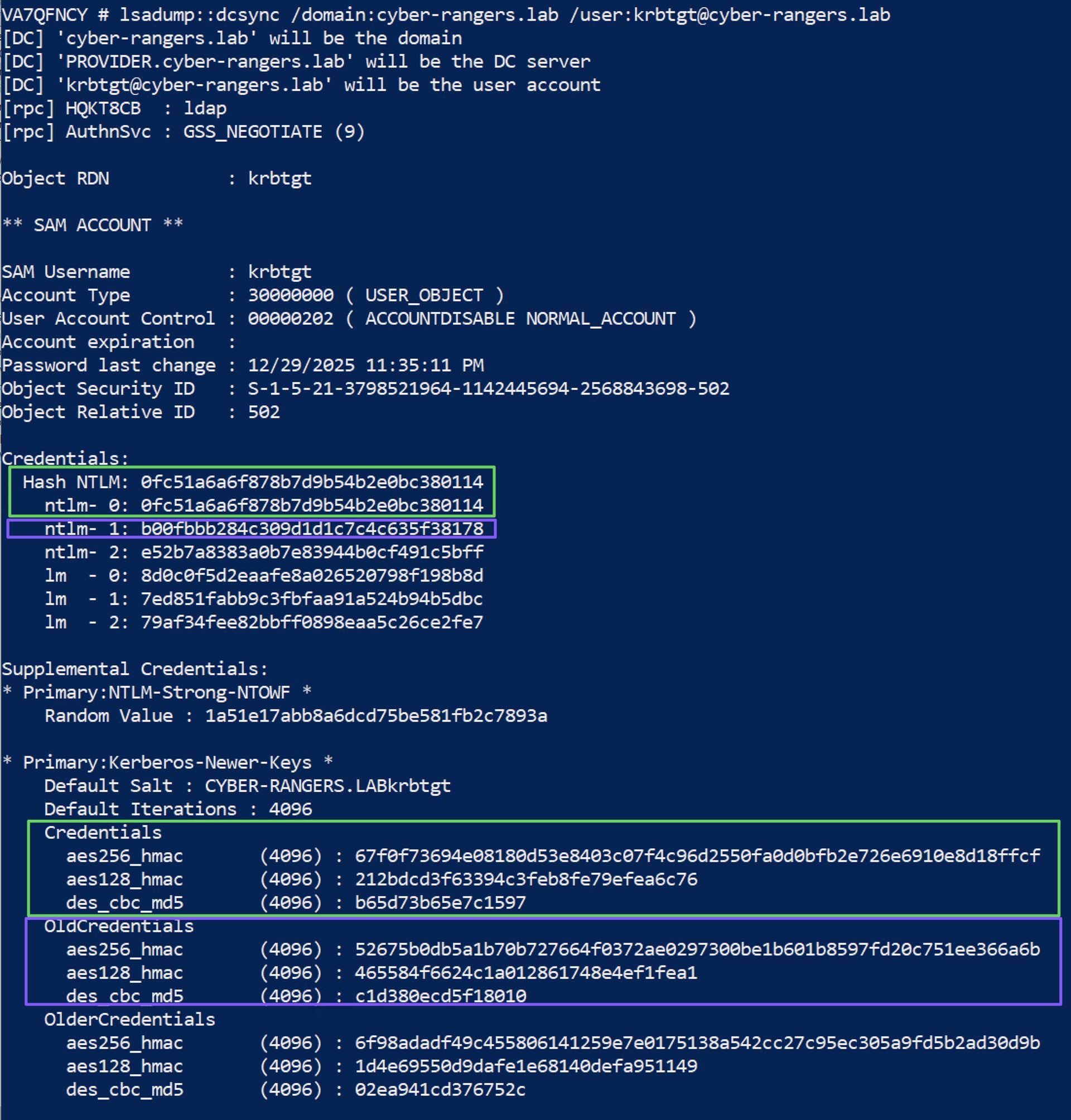

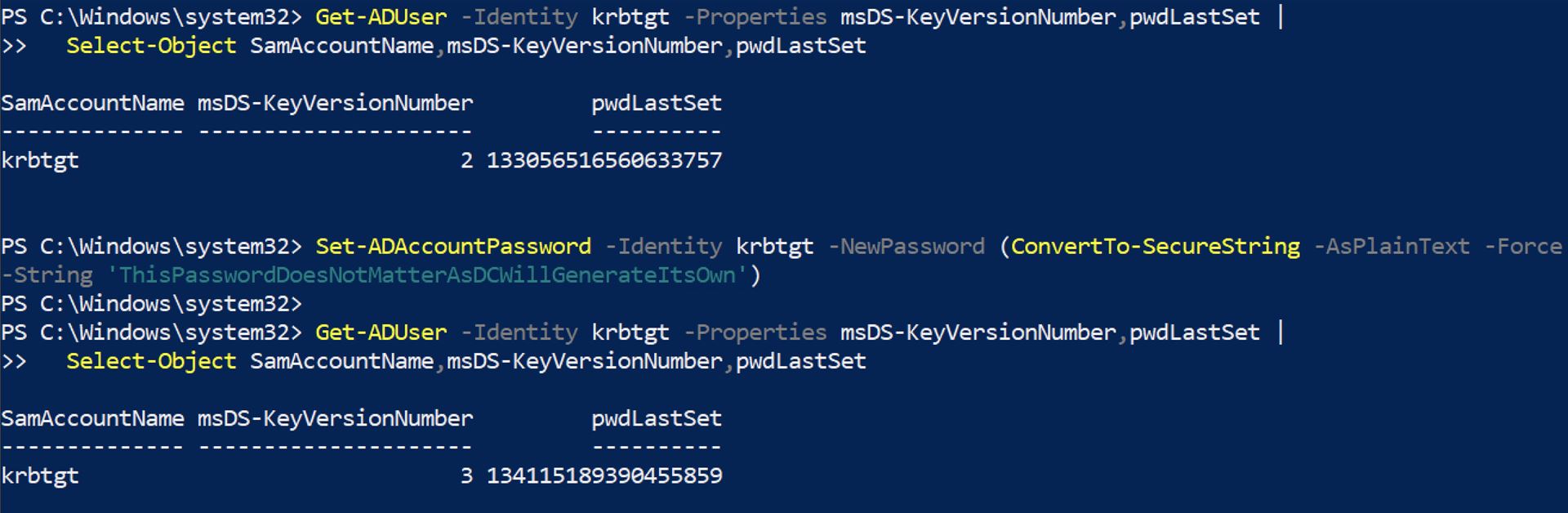

KVNO and msDS-KeyVersionNumber

KVNO (Key Version Number) indicates which version of a key was used. In AD, it effectively tracks key material changes (password changes). Microsoft defines msDS-KeyVersionNumber as “Kerberos version number of the current key for this account.”

The AD Kerberos key model (what KRBTGT protects—and what it does not)

Most operational and incident mistakes come from mixing up three different key planes. You should treat them as separate “cryptographic axes”.

KRBTGT key (domain key for TGTs)

The KRBTGT key is the long-term key derived from the KRBTGT account password in a given domain. The KDC uses it to protect TGTs (the ticket for krbtgt/REALM). The practical consequence is straightforward: compromise of the KRBTGT key compromises the domain’s ability to trust TGTs as domain-issued credentials. Each AD domain has a KRBTGT account used to encrypt and sign Kerberos tickets for the domain.

Service account key (key of the target service)

A service ticket is encrypted with the long-term key of the target service (service account key, or computer account key for services running under LocalSystem on a member server). Resetting a service account password affects that service’s tickets, not the entire domain’s TGT trust.

Trust secret / inter-realm key (key of a trust relationship)

Cross-realm scenarios rely on the trust secret stored in the Trusted Domain Object (TDO). Microsoft explicitly notes that key versioning for trusts is stored in the trusted domain object, not in msDS-KeyVersionNumber of ordinary accounts.

Operationally: resetting KRBTGT does not reset trust secrets; resetting trust secrets does not reset KRBTGT.

RODC: cryptographic isolation by design

A Read-Only Domain Controller uses a dedicated KRBTGT account (commonly krbtgt_#####) and therefore a separated key space, which limits the blast radius of an RODC compromise compared to a writable DC compromise.